A tiny, often overlooked creature, commonly sold as aquarium food, is playing a crucial role in mitigating global warming through a remarkable migratory process. These “unsung heroes,” known as zooplankton, gorge themselves in the spring and then descend into the depths of the Antarctic Ocean, where they metabolize the fat they’ve accumulated. This natural process sequesters as much carbon as the annual emissions from approximately 55 million petrol cars, according to recent research.

The discovery, led by Dr. Guang Yang from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, has surprised scientists by revealing the significant amount of carbon stored by the Southern Ocean, prompting a reevaluation of its role in global carbon cycles. Dr. Jennifer Freer of the British Antarctic Survey describes zooplankton as “unsung heroes” due to their unique lifestyle, which starkly contrasts with more famous Antarctic animals like whales and penguins.

The Hidden Life of Zooplankton

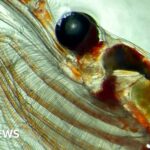

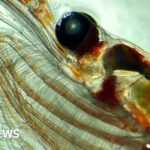

Zooplankton, such as copepods, are minute creatures ranging from 1 to 10 millimeters in size. They are distant relatives of crabs and lobsters and spend most of their lives in a state of dormancy, residing between 500 meters and 2 kilometers deep in the ocean. Prof Daniel Mayor, who has photographed these creatures in Antarctica, notes the visible fat reserves within their bodies, which play a crucial role in their survival and the planet’s climate regulation.

Globally, oceans have absorbed 90% of the excess heat generated by human activities, with the Southern Ocean accounting for about 40% of this absorption. Much of this is attributed to zooplankton, whose carbon-rich waste sinks to the ocean floor, a process previously understood only in part. The latest research focused on the seasonal vertical migration of copepods, krill, and salps, which consume phytoplankton that transforms carbon dioxide into organic matter through photosynthesis.

Quantifying Carbon Sequestration

The study calculated that the seasonal vertical migration pump transports 65 million tonnes of carbon annually to depths of at least 500 meters. Copepods contribute the most to this process, followed by krill and salps. This carbon sequestration is comparable to the emissions from 55 million diesel cars, as per the US EPA’s greenhouse gas emissions calculator.

Researchers have delved into historical data dating back to the 1920s to quantify this carbon storage. Dr. Freer and Prof Mayor recently spent two months aboard the Sir David Attenborough polar research ship near the South Orkney Islands and South Georgia, collecting zooplankton samples under challenging conditions.

Challenges and Future Implications

Despite their critical role, zooplankton face threats from climate change, warming waters, and commercial krill harvesting. Prof Atkinson warns that these factors could reduce zooplankton populations and limit carbon storage in the deep ocean. In 2020, krill fishing companies harvested nearly half a million tonnes of krill, a practice permitted under international law but criticized by environmentalists.

The new findings underscore the importance of incorporating zooplankton’s role into climate models to better predict future warming. “If this biological pump didn’t exist, atmospheric CO2 levels would be roughly twice what they are now,” explains co-author Prof Angus Atkinson. The research, published in the journal Limnology and Oceanography, highlights the oceans’ vital function in mitigating climate change.

For those interested in staying informed about climate and environmental news, the Future Earth newsletter offers exclusive insights delivered weekly by the BBC’s Climate Editor, Justin Rowlatt.

Zooplankton’s Role in Combating Climate Change Unveiled

Zooplankton’s Role in Combating Climate Change Unveiled Zooplankton’s Epic Migration: A Hidden Ally in Combating Climate Change

Zooplankton’s Epic Migration: A Hidden Ally in Combating Climate Change Avoid These Costly Mistakes When Buying Phones, TVs, and Gadgets

Avoid These Costly Mistakes When Buying Phones, TVs, and Gadgets Yulia Putintseva Requests Spectator Removal at Wimbledon Over Safety Concerns

Yulia Putintseva Requests Spectator Removal at Wimbledon Over Safety Concerns Exploring Canadian Cuisine: A Culinary Journey Across a Diverse Nation

Exploring Canadian Cuisine: A Culinary Journey Across a Diverse Nation