In a groundbreaking study, researchers have uncovered how human fishing practices have dramatically altered Caribbean reef ecosystems over the past 7,000 years. Fossilized coral reefs from Panama’s Bocas del Toro Province and the Dominican Republic reveal a significant decline in shark populations and a shift in fish community dynamics. The findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, highlight the profound impact of human activity on marine food webs.

The study, conducted by scientists at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), analyzed ancient reef fossils, discovering that shark populations have plummeted by 75%, while fish species targeted by humans have become 22% smaller. Meanwhile, prey fish species have flourished, doubling in numbers and growing 17% larger. This shift underscores the “predator release effect,” where the removal of top predators allows prey populations to thrive.

Reconstructing Ancient Marine Ecosystems

When we think of fossils, images of dinosaurs often come to mind. However, the fossil record also preserves the remains of smaller organisms, such as fish and corals, offering insights into the history of our oceans. The STRI team meticulously studied exposed fossilized coral reefs, which date back 7,000 years, providing a unique glimpse into pre-human impact Caribbean reefs.

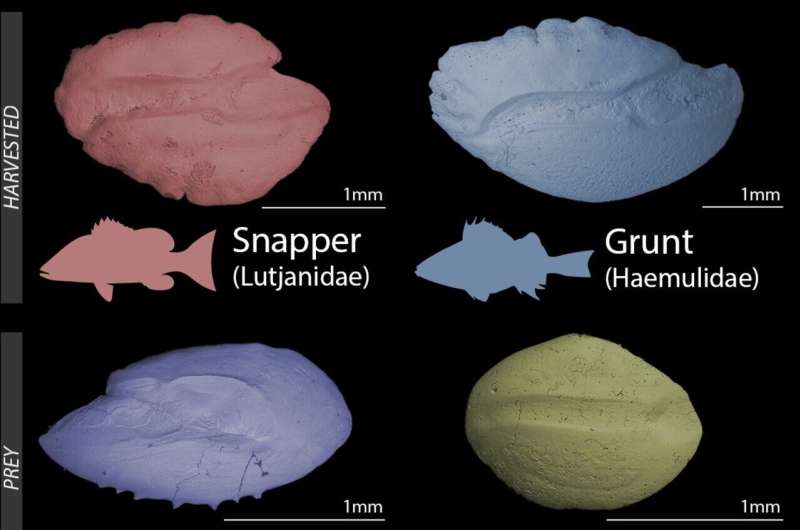

Within the fine sediments of these ancient reefs, scientists uncovered thousands of fish ear bones and shark scales, enabling them to reconstruct entire ancient fish communities. By examining 807 shark denticles and 5,724 fish otoliths, they were able to compare ancient ecosystems with modern reefs, revealing dramatic shifts in fish community structures over millennia.

Evidence of Predator Loss and Prey Release

The research provides the first historical evidence for the predator release effect in Caribbean reefs. While scientists have long predicted such an effect, evidence was scarce without a baseline of what reefs looked like before human interference. The study’s findings demonstrate how the loss of top predators, such as sharks, cascades through the entire food web, altering the balance among coral reefs.

“Sharks have declined by 75% and human-targeted fish have become 22% smaller. Prey fish have doubled in abundance and grown 17% larger on modern reefs.”

Implications for Conservation

This study not only sheds light on historical changes in reef ecosystems but also holds significant implications for future conservation efforts. By revealing what Caribbean reefs looked like before intensive human fishing, these ancient fossils provide a critical baseline for understanding the natural state of coral reef food webs.

Remarkably, the tiniest reef fish, which shelter in coral crevices, showed no change in size or abundance over thousands of years. This stability suggests a resilience to changes occurring at higher layers of the food chain, offering hope for certain aspects of reef ecosystems despite widespread environmental degradation.

Future Directions and Conservation Strategies

The findings underscore the importance of protecting top predators and managing fishing practices to restore balance in marine ecosystems. As scientists continue to uncover the historical dynamics of coral reefs, these insights will inform conservation strategies aimed at preserving biodiversity and ensuring the health of marine environments.

Looking forward, the study highlights the need for further research into the long-term impacts of human activity on marine ecosystems and the potential for restoration efforts to mitigate these effects. By understanding the historical context of reef ecosystems, conservationists can develop more effective strategies to protect these vital habitats for future generations.

For more information, refer to the study by Aaron O’Dea et al., Prehistoric archives reveal evidence of predator loss and prey release in Caribbean reef fish communities, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.